An estimated 300,000 “war brides,” as they were known, left home to make the intrepid voyage to the United States after falling in love with American soldiers who were stationed abroad during World War II. There were so many that the United States passed a series of War Brides Acts in 1945 and 1946. This legislation provided them with an immigration pathway that didn’t previously exist under the Immigration Act of 1924, which imposed quotas on immigrants based on their nation of origin and strategically excluded or limited immigration from certain parts of the world, particularly Asia.

Equipped with little but a feeling and a sense of promise, war brides left everything that was familiar behind to forge a new identity in the United States. Many spoke little to no English upon their arrival in the country, and they were introduced to post-war American culture through specially designed curricula and communities. To this day, organizations for war brides in the United States provide networks for military spouses and their children, helping them keep their heritage alive and share their experiences of their adopted home.

To commemorate the 75th anniversary of the end of World War II on September 2, 2020, Babbel conducted interviews with surviving war brides as much of the world endured lockdown. Many of these women are now in their 80s and 90s, and their oral histories celebrate the challenges and successes of adapting to a new culture and language, as well as reflect on the leap of faith they all took to travel across the world to an unknown country. Spoiler alert: there are few regrets.

Below, you’ll find our curated repository of the video, audio and transcription of the conversations we had with war brides from Japan, France, Belgium, Italy and the Philippines, as well as photographs they’ve provided us from their past and present.

Skip ahead to:

Alice Lawson’s Story (Belgium)

Nina Edillo’s Story (Philippines)

Emilia Zecchino’s Story (Italy)

Huguette Coghlan’s Story (France)

Tsuchino Forrester’s Story (Japan)

War Brides: On Coming To America

Alice Lawson — Belgium

I was born in Belgium, in Liège. I lived in a suburb, on a high plateau that overlooked the city. I had family that lived in the countryside, in the Flemish part of Belgium, so I knew Flemish. I also studied German because I was worried about the war coming, which started when I was about 16 years old.

I remember when I was a young girl and the Germans were coming into the city. They would crawl up the hillside with rifles in their arms, and the kids who were at the top of the hill would throw clumps of grass or rocks to try to dissuade the Germans from coming up the hill.

One soldier came into my parents’ house because he was hungry. My father said, “Come in the back and you can eat something.” However, the German wouldn’t eat anything unless my dad ate the same thing with him.

My dad worked on the streetcar system where he was a conductor, and he got me to work there as well. I was one of the people in the back who moves the electrical lines to the next one over. I also worked in the garage getting things started, moving the trolleys onto the line. I was tough.

I met my husband when the Americans came in. We went to the movies, my mother and I, and he was on the other side of the road. He looked at me and then came over and presented himself. That was it. Then we started dating.

He was an American soldier, so he spoke only English. We had things in common because I was a nurse working in the Belgian hospital and he was an American working in the American military hospital. So we had a connection in that regard, but I think the main connection had to do with the way that I looked and the way that John looked. He was good-looking, so I was willing to date him.

He wanted to get married right away. He had to go approach my father to ask him if he could marry me. And he was, of course, very reluctant, but I would not be dissuaded.

Once we decided to get married, he did a very unusual thing for an American soldier: he had my sister take all my measurements and sent them to his sister who lived in Maine, and he asked her to pick out a wedding dress for me and send it to Belgium. He also paid for the flowers and things like that so that we could have a beautiful wedding, which I think is pretty unusual.

Once we decided to get married, he did a very unusual thing for an American soldier: he had my sister take all my measurements and sent them to his sister who lived in Maine, and he asked her to pick out a wedding dress for me and send it to Belgium. He also paid for the flowers and things like that so that we could have a beautiful wedding, which I think is pretty unusual.

At the time, I said to him, “I’m Catholic. Ff I do get married, I want to be married in a church.” So he said, “Well, I’m Catholic too.” I said, “Well, tell me a few things about the Catholic religion.” And he couldn’t tell me anything! He only knew how to do the sign of the cross like a Catholic — that’s all he knew. So he took a course in the army to become a Catholic for me.

We went off for a two-week honeymoon in the countryside of Northern Belgium. But because the war was still going on in Japan, he was then transferred there. I was only a few months pregnant when he got sent off to Japan.

The war ended before he got there, so he was sent back to the United States and released. He had made arrangements for me to come to the United States. But when my dad found out I was moving to America, he passed out. It was tough on the family, but my husband had made a promise that we’d be coming back to visit. Of course, that didn’t quite happen as well as my mother had hoped. It was tough on my parents, which made it hard for me.

I went through the Ellis Island immigration area when I arrived, and I spent a night in New York before getting on a train. It took five days to get to Alabama. I didn’t recognize my husband when I arrived because he had gotten very sick and lost so much weight.

It was a different way of life for me because I grew up in the city, had season tickets to the opera, and was an art student in college. Now I was in rural America facing an outhouse: there was no indoor plumbing, no indoor running water. We ended up moving into a chicken coop that my husband covered inside with paper so that nobody could see in.

I was also in a dry county, and I had a bottle of wine that I brought from Europe. I put it in the window to cool, and my husband saw it when he was coming home, and said, “You’re going to get us arrested! You’re not allowed to drink wine in this county!” So I said to him, “Why, are we in Russia?”

I had a couple of sisters-in-law who were very good to me. My mother-in-law as well. So they tried to accommodate me and teach me English, and my husband would give me homework every day to study the language. Of course we didn’t have TV or anything, but I would learn through the people who I met.

My English wasn’t good — there were a lot of hand signals at that time! It was difficult to learn, but I credit my ability to learn to the fact that I knew Flemish and German. There are a lot of French words that are English words. Between those three languages, I felt that I had a leg up on learning the English language.

Many times, people would call me an immigrant and say, “You’ve got an accent, go back to your country.” I remember those kinds of comments, but I could shake them off. They didn’t bother me.

I was pretty surprised by the racial problems I confronted in Alabama. I couldn’t understand that kind of racism because I wasn’t used to that in Belgium.

I was once on the bus and there was no room at the front of the bus to sit. I had my son in my arms and my husband was also on the bus, the three of us. I went to the back of the bus to sit because there was an empty seat, and my husband was very upset with me, that I would do that and not stand at the front. Those kinds of encounters were part of daily life for me.

We lived in Alabama for about a year or so. But because I was so unhappy with the lack of city life, and there was no work down there for my husband, we went up to join my sister-in-law in Michigan and get a job at one of the factories.

My husband worked bartender jobs and we lived in terrible housing, but he ended up getting a job at General Motors. One day, I went off with some friends on a Sunday drive and I saw a sign that said “GI homes for $5.” So I gave the guy $5, went home and told my husband, “Oh, I bought a house today!”

He said, “You bought a house?! Alice, do you know what you’re saying?” I said, “Yeah, I bought a house.” So we took a bus over there and we went to see the guy with my husband’s discharge papers, and we got the approval for buying the house! This is the house we’re still in today, since 1950.

We lived right on the main line for a streetcar in Detroit, so we were 10 minutes away from downtown. My daughter was born two years after my son, and I would take my children into the city frequently. In Detroit, I felt more acclimated to living in America, once I got into the city routine. I’ve always been a city girl, that’s just how I roll!

We lived right on the main line for a streetcar in Detroit, so we were 10 minutes away from downtown. My daughter was born two years after my son, and I would take my children into the city frequently. In Detroit, I felt more acclimated to living in America, once I got into the city routine. I’ve always been a city girl, that’s just how I roll!

I’ve been back to Belgium a few times since. I got married in 1945 and went back in 1950. Then in 1964, when my son graduated from high school, I took him back to meet his relatives in Belgium, because he was just a baby when he left there. The last time I was there was in the early 2000s.

I still manage to speak French — je parle toujours le français ! I have a small circle of friends, and we go to lunch and chitter chatter away speaking French. I had other friends who were from Belgium, but they have since passed. I still carry the Flemish language within me, but don’t have much of an opportunity to speak it to anyone around here.

I’ve noticed with other war brides that they were very eager to be accepted and to acclimate into society, so they don’t necessarily talk much in their native language. I just went along with everything that was happening here. I didn’t try to change anything. I just helped myself and learned English. People would always say, “Oh, you have an accent,” and I would reply, “Yeah, vous parlez français? Do you speak French? That’s why I’ve got an accent!”

For people who are considering moving abroad to marry someone, I would say, “Join the club!” If you love somebody, you want to do anything you can to be with them.

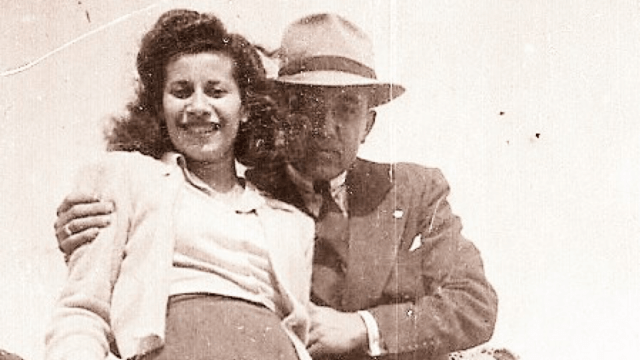

Nina Edillo — Philippines

Content warning: some of the written and video material below contains graphic accounts of war-related violence.

My full name is Antonina, but I go by Nina. I’m 92, almost 92 and a half. I was born in Manila and we lived in a compound where the superintendent of city schools also lived. There were several American teachers and their families in that compound, so we were speaking English a lot.

Growing up wasn’t easy, because the war broke out when I was in seventh grade. They had sentry boxes every few miles, and everyone who passed by had to bow. And if you didn’t bow correctly, they’d slap you. The Japanese would come out of the sentry box and slap you and show you that this is the way to bow to them. So my dad said, “Don’t go outside if it isn’t necessary.”

During the war, our house was burned down and we had run for our lives because the Japanese were trying to kill as many civilians as they could while the American soldiers were pursuing them. We tried to shelter in one of the burned-out houses, and we went under the foundations to try to hide. But before that, we had to cross a big wall. It took me a long time to get in through the passage, and a Japanese soldier came over to me and poked me in the back with his bayonet. That’s why even now, I don’t want anyone touching me from the back. It has remained with me. I was so scared. I was 13, 14 at that time.

That night we could hear the Japanese yelling and running and then at around 2 or 3 o’clock when it started getting light, I saw a pair of feet. I knew that the Japanese did not have boots like that. And then after a while, I said, “Oh my God, these are different. These are big feet.” One of the soldiers bent down and said, “Oh, hello there.” When he said “hello,” I knew he was an American!

He told us we were in the firing line and to go as far back as we could. I was so excited. I said, “The Americans are here!” While I was running I looked down, and I didn’t realize that I was running over dead bodies. I said, “Please help me, dear God, help me.” I couldn’t walk anymore because I saw so many of them. And I was in the midst of them. Dead people. That was terrible. I still occasionally dream of that, and then I can’t sleep.

Eventually, we were able to get to a Red Cross station. They were standing there serving cookies and food, so we grabbed some and ate like there was no tomorrow. Thank God we didn’t get sick when we ate, especially me!

It was in early 1945 that I met my husband. We hadn’t seen the ocean for three years, so my sister said, “Let’s go and see how the beach is.” That was where we met a few soldiers, and my sister said to me, “Don’t say anything. I’ll do the talking!”

They introduced themselves and said they were Filipinos from the United States, and they said that they wanted to meet some of the Ilocano, which is my parents’ language and dialect.

They asked, “Would you like some candy?” Well, God, due to the war I hadn’t tasted candy for years! So they gave us some Hershey’s candies, and that’s why some of the war brides call me “Hershey Girl!”

A month after that I met my husband, in May 1945. I didn’t know who he was at that time, but he walked in singing “Sleepy Lagoon.” My sister said, “Oh, he has a beautiful voice.” I said, “No, he can’t sing!”

He was a Filipino man in the U.S. Army and could speak the same dialect that my parents spoke. He was very nice and polite, and they liked him.

We married on December 2, 1945. It was in a small church, and I wore a short dress that my friend made for me. We didn’t have buttons, so she found what looked like little pebbles that she covered to make the buttons. We didn’t have zippers or anything like that, so it was buttons all the way down the back. Another friend had found an old Communion veil that her daughter wore, and they made that into my little veil.

We married on December 2, 1945. It was in a small church, and I wore a short dress that my friend made for me. We didn’t have buttons, so she found what looked like little pebbles that she covered to make the buttons. We didn’t have zippers or anything like that, so it was buttons all the way down the back. Another friend had found an old Communion veil that her daughter wore, and they made that into my little veil.

When my husband finished his tour of duty in Japan, we came home to the United States. I had two children at that point, who were both born in Tokyo.

In Tokyo, my children learned to speak a bit of Japanese, and I couldn’t understand them. They would come home and tell me things in Japanese, and I would say, “Just speak in English. I don’t understand Japanese!” They would laugh. They had such fun doing it.

When we came to America, we arrived in San Francisco. I was seasick the whole time, so I was anxious to get off the ship. But we sailed under the Golden Gate Bridge at night, and it was all lit up, and it was just beautiful.

The first thing that struck me about San Francisco was the cars. There were so many cars! They were just whizzing by. In Japan, there were not many cars around. Usually, the soldiers were the ones who had cars — and some of the richer Japanese people — but the Japanese tended to rely on streetcars and the subway. It was 1954, and San Francisco seemed so bright and crowded.

The way people spoke in America was also very different. In Japan they don’t speak slang, and it took me a while to understand American lingo.

My husband eventually found a job in Los Gatos, California, for the Sisters of the Holy Names of Jesus and Mary. He worked for them as a second cook, and they provided us with a home.

Los Gatos was a very small town at that time. There were barely 5,000 people living there. We were the only Filipinos in that area, and they did not know what to make of me. When I took my eldest daughter to kindergarten, the children would say, “What are you? Chinese, Native American?” And I said, “No, we’re from the Philippines!” They didn’t have any idea where that was.

I was a seamstress for the convent the whole time. I made habits out of thick wool. There was a lot of hand sewing involved, and making the skirt required about five yards alone that I had to pleat to fit each person, and it was heavy!

On the whole, people were very nice. I missed my parents, but my sister ended up coming to America as well. I get to speak Ilocano with her still, which is nice because I haven’t been back to the Philippines since 1950. It was too expensive to travel back when I first came to America. I regret that, though. I don’t know if I’m strong enough to travel now.

For me, America hasn’t really changed from the time when I first arrived, because the way people of color are being treated now seems to be the same as when I first got here.

Technology, though, is one change that is so overwhelming for me. Going to the moon left me in awe. And my massage chair — I like my massage chair.

My advice for young people moving to another culture or country is: love conquers all. That’s my philosophy. I loved my husband and he loved me, too. He took good care of me. I miss him so much. We were married almost 57 years. It was fun to hear him sing.

Emilia Zecchino — Italy

I was born in Bari, Italy. Times were slow during the depression, and I had a very complicated life. When I was a little girl, my dad was in the army, and he was sent to Ethiopia. In 1935, he brought the whole family over there, so I lived in Ethiopia for about five years, and I returned to Bari right in the middle of World War II.

Before the war, I loved to read a lot. I used to love going to school. But my father was a prisoner of war for six years, and while we were in Ethiopia, we lost everything. We were in a concentration camp. And by the time we got back to Italy, it was 1943, and things were very different from when we left.

The war had changed everything in Bari. I remember running because of all the bombings. Until the British and American armies came to Italy to set us free, things were very hard.

I met my husband in a very exceptional way. My husband was of Italian descent, and he had gone to America when he was a young boy, but he still had family in Italy.

He contracted a disease while serving America in the Pacific War, and he had to go back to the veterans hospital in America. While there, his mother, who was in Italy, became very sick.

It took him 20 days by boat, but by the time he reached his family, his mother had already passed away. He stayed in Italy with his family for a few months.

During this time, I had found a job with the American army in a rank called the USO Shows, which brought in celebrities to perform for the troops. There was an office in Bari, and they needed a typist. I was only 17 years old, and I did not speak English, but I could read it. They convinced me I did not have to speak to anyone, just type. So I copied the words.

My husband passed our door and saw me, and he said he wanted to see more of me. He waited until the end of the day, and then he called me. He called after me in Italian, and I said “Yes, what can I do for you?” He asked me how to get to the station, explaining he was new in town. I tried to explain, but decided to walk him there. And that’s how we met.

As we started talking, we found out we had quite a few things in common. He was born in the same town as my father, and he knew some family there. Actually, my father’s cousin was my husband’s doctor!

That day we met, we felt a special attraction for each other. When we fell in love, it was as simple as that. He had to go back to the Veterans Affairs hospital in America, so we planned to get married after he returned to Italy. But he ended up staying in the hospital for almost a year. By that time, his finances were low, and he told me he did not think he could return to Italy. But he told me there was a way I could come to America as one of the war brides, and we could get married in America.

It took a lot of thinking on my part. But you know, I thought it was meant to be, so I said, “Okay, I’ll try.” My parents were not pleased about it, but I wanted to marry him. They put up a good fight because we did not know anyone in America. How could they let their 19-year-old daughter go alone to a strange country? I had to do a lot of convincing, but I was in love with him and he was in love with me.

I arrived in New York Harbor in 1947. I had seen lots of movies where the city was portrayed as such a prominent and beautiful place to live. I had no idea what skyscrapers looked like in real life, but when I saw them, it was really extraordinary.

Everyone was so friendly and kind when I arrived. I felt very much at home. My husband opened a grocery store soon after, and he put me behind the counter. That’s when I realized that I had to learn English. We had all kinds of people come through the door: Black, white, young, old, Italian — every nation! I didn’t know how to speak English, and they all helped me. We all got along beautifully.

I remember someone told me about an area called Little Italy, where they had bookstores filled with books that would teach me languages. I read them every day and I made a point of practicing my English, even though I made a lot of mistakes at first. I sometimes made very stupid mistakes! Some people laughed at me, but I laughed with them. I asked them to correct me when I made mistakes, because that’s the way I learned.

After a couple of years of only speaking English with my husband, I knew how to speak well. I loved the language. English is beautiful. I remember reading Joseph Conrad. I found some of the phrases he used so attractive. Once I started reading in English, I felt like part of the environment. I was not a stranger any longer. The sooner you learn the language, the more you feel at home. I wanted to assimilate into the American lifestyle.

One of the biggest differences that struck me was that in Italy, if there was ever something special happening, you would get a mob arriving. Everyone would fight to get to the front of the line, whereas Americans used to line up for hours — there was no pushing, no shoving, no nothing.

The one thing I miss about Bari is the food, because everything is very organic. They still do things the old way, and you can’t replicate that in America. And the wines that they grow in the Bari regions, where the fruits are picked straight from the tree — you can’t make them here.

I went back to Bari almost 10 years ago with my daughter for the first time. I couldn’t go back sooner because of the business, the children, and my husband being in and out of the hospital.

It was very emotional because it did not look the way I remembered. It was all completely different, but the food and the restaurants have stayed the same. But it felt so normal to be there. You never lose your birthright, and I was so happy to see my cousins.

I didn’t teach my children Italian, and that was one mistake I made. I wanted to learn how to speak English, so I never spoke Italian to them. I brought my whole family to America, though. My mother raised my oldest son, and only spoke Italian to him, so when he went to kindergarten he couldn’t speak English! The nuns called me and said, “You cannot leave this boy here. He’s crying all the time. He doesn’t understand us.” So he stayed at home, and I had to teach him English.

For people considering moving to a different country or culture, I would say to be courageous, because you never know what you’re going to encounter.

If they are fortunate like me, they will find a beautiful place to call home. My husband was a good provider. I had no problems. We just had to work hard. You’ll have to assimilate with the people wherever you’re going. If you want to keep your ways, then you’re always going to feel like a stranger.

Huguette Coghlan — France

My maiden name is Huguette Roberte Fauveau, and I am now 95 years old. I was born in Courbevoie, a suburb of Paris, and grew up in a nearby suburb called Chatou. I moved to America with my husband in 1946, and I still live there now.

I had a happy childhood before the war. My parents eloped when they were about 20, and they had me and my younger brother, Serge. My dad worked in a factory as a tool and dyes maker. They did not have a lot of money in the 1930s.

During the war, I remember bombs falling very close to my home. So close that my dad, my brother and I all lost our hearing. It eventually returned, but as I have gotten older, I have lost my hearing again.

We were blessed that we did not get hurt during the German occupation. My grandparents had a little farm, so food was not scarce. We always had food to eat, but bread was something we did not have enough of. At one point, the Germans took over the factory where my father worked. While we remained unhurt, I heard and saw terrible things.

I met my husband when I was on vacation with my grandparents. I was walking to a dance with my friend, Jacqueline. We had missed our ride, so we had to walk over a mile in our high heels. While we were walking, a large Jeep stopped next to us and asked if we wanted a ride.

Naturally, we said no. When we eventually arrived at the venue, our feet were a little bruised, but this did not stop us from dancing. I noticed that two soldiers came in, and after a while, one of them approached me. I knew it was one of the men from the jeep. He told me I had nice legs, and we talked for a long time after that. He told me he was part of the military police and was tasked with supervising the dance. His name was Rodger Murray Rusher and he was 20, like me. He asked me if I would go on a date with him the next day, so I told him where I lived and said yes, but I never thought he’d find my house. He did.

My parents and my brother, Serge Lucien, liked Rodger straight away.

My parents, and above all my brother, were extremely sad when I told them I wanted to move to America. But they loved and trusted Rod. His mother had written a letter to my mother, so they had faith that he and his family would take care of me.

I married Rod in Chatou on the 23rd of September, 1945, in the Sainte-Thérèse Church.

I had studied English for four years in school, so I could read and write English. I was pretty good at speaking it, but I spoke with a strong French accent. When I got to America, I discovered that some people had a hard time understanding me. Many still do!

I became keen to learn English. I remember I read a lot, did lots of crossword puzzles, and always had my nose in a dictionary. It didn’t take me long to become fluent.

Rod and I first arrived in New York on the 19th of May, 1946. I spent my 21st birthday in New York. After that, we traveled to where Rodger’s family was from — a place called Roundup, Montana.

My extended family made me feel very welcome when I arrived, and they hosted a party to introduce me to all their friends from around the town. They all wanted to hear about France, and all were very nice and welcoming. Up until then, I’d thought my English was good, but this is when I discovered that I had a hard time understanding them, and vice versa.

My in-laws had a four-bedroom log ranch. They did not have electricity, and their water came from a well. The bathroom consisted of two holes in a little outhouse. It was a very pretty ranch, but it was a shock for me. I came from a very modern house in a big city. But when you are young, you adjust easily to changes.

I have returned to France many times over the years. The first time was not long after Rod died. He wanted to be a pilot, and he was learning to fly under the GI Bill. When I was still pregnant with our second child, Rod was killed in a plane accident with his brother in 1948.

A year or so after that, I returned to France. I stayed for six months, and then made the very difficult decision to return to America. It was hard to leave my parents and brother again, but by then I knew that I wanted my children to be American.

I didn’t have any formal lessons to learn how to be an American, but I soon grew to love America very much.

In Roundup, I missed the symphony and the opera that I used to attend at home. But when I moved to a bigger city in Montana, Bozeman, I could start to enjoy them again.

I spoke French with my children at home. My first two children were born in Roundup. I remember once overhearing some other children make fun of Gerald and Gregory for speaking French, so that’s when I thought, “No more French. They are American, they live here, and I want them to be American!” That was a mistake, but I didn’t know it then. It was difficult as a widow, and things were very different back then.

Three years after Rodger died, I remarried to a man named Terry James Coghlan. We had a girl, who we named Jacqueline. She speaks a little French, is very keen to learn, and is taking lessons now!

I would tell people who were considering moving to another country for love to not be afraid, and to follow your heart.

Tsuchino Forrester — Japan

I came to America in 1960. Washington is such a beautiful state, with its mountains, oceans and rivers. In many ways it reminds me of Japan, and that’s why I settled here. There’s also a strong Japanese community in Seattle, where my husband and I have settled.

I was born in the countryside of Japan, so I would run around a lot and study little. I remember playing all the time with no restrictions.

I was born in the countryside of Japan, so I would run around a lot and study little. I remember playing all the time with no restrictions.

When the war started, I was about 10 years old. We were in the countryside, and we had a ranch, so we didn’t have a problem feeding ourselves. Maybe a bit with meat and fish, but we produced our own rice and vegetables, so we were never hungry. I don’t remember seeing any soldiers, and we didn’t get bombed. Maybe 20 miles from my house was a city, Fukuoka, and one time I remember seeing the bombs from afar. To me it looked like fireworks. That’s what I remember.

I met my husband, Michael Forrester, through a mutual friend. He was in the U.S. Air Force. One night, he was visiting his friend, and by chance, I was visiting his friend’s wife, so that’s how we met.

At first, I thought he was a snob like all the other American soldiers who came to Japan. You know how soldiers come in and take over our country and we couldn’t say anything. He thought he was a big shot, so I thought I would show him my Japanese spirit!

That changed when he showed how persistent he was. He kept coming back, and the Japanese guys, they never did that. And he had plans for his life. I liked that about him. The way he looked to the future of his life — that’s what I fell in love with. He wanted to become a pilot, and I wanted to help.

When my father died, my brother quit school to become the head of the family. At that time in Japan, women weren’t supposed to be more educated than the head of the family, so my mother wouldn’t let me go to college. My teacher even tried to talk to my mother to convince her, but she still said no. So with Mike, and his plans, I said, “This is someone I can help go to college.” And now we’ve been married 62 years.

Initially, my family were not happy about me wanting to marry an American. Some of my family had died in the war, so my uncle was strictly against Americans and those who associated with them. He disowned me. But my other family members, they knew how stubborn I was, and they knew that once I had made up my mind, that was it. Their only worry was how would they help me if I was so far away.

We married in 1958. There were a couple of things in our way. When we filed for permission with the U.S. Air Force to marry, they sent Mike back to the United States! So it took time — close to two years. When he managed to come back to Japan, he was stationed.

We married in 1958. There were a couple of things in our way. When we filed for permission with the U.S. Air Force to marry, they sent Mike back to the United States! So it took time — close to two years. When he managed to come back to Japan, he was stationed.

We actually had three weddings. The first was in a Shinto temple, which the Japanese recognized as an official marriage, but the Americans did not. It made it easier for me to move with Mike to his new station on Okinoerabujima. Then our second wedding was December 23, 1958, and our chaplain one was on February 17, 1959.

Our first wedding was a Japanese wedding, which meant you have to take your shoes off, and that’s when I saw that Mike had holes in his socks! I remember looking at his feet and saying, “What is this?”

The U.S. Air Force found out about our Shinto wedding, and they didn’t like it. They almost court-martialed Mike for it. But his mother wrote to President Eisenhower, who stopped it.

We moved ahead with our plans to move to the United States. I had gotten my visa and passport, and Mike was due to finish his service in the air force. One night, the MP and Japanese police knocked on my door, and I thought, “What now? Is Mike going to jail again?” But this time, it was the sad news that Mike’s father had died. So Mike had to leave straight away.

It actually turned out that even though Mike left before me, I arrived in America two days before him. The American Red Cross helped me with getting the right tickets and everything. When I arrived in New York, I slept in the same bed as his mother, because there was no space for me.

Because it all happened so fast, I didn’t have a chance to feel sad about leaving Japan. It was more about how I could get there safely. And I was young, so my mind was made up. I’d heard great things about America. It was the land of opportunity.

I know a lot of Japanese people who miss Japanese food, but I don’t miss much about Japan. I liked hamburgers, and steak, and Mike’s mom’s specialty was spaghetti. That was good!

I learned how to read and write English a little in Japan, but the pronunciation was difficult for me. Some words were easy to confuse, like “yard” and “garden.” When I arrived in America, I had three younger brothers-in-law. I had to learn how to speak English for my own survival. I was always listening in the beginning, and I found that was the best teacher.

We moved around America a lot. When I first came, I felt so free and energetic. I love it here. Nowadays, I think people forget to show kindness and manners, however, which saddens me.

I have been back to Japan many times since. It has changed a lot. Especially my village. We used to run through all the houses playing hide and seek without permission. But now all the houses have fences, and gates, so it must be different being a child there. And there are lots of multistory buildings. Everything is being built up.

I think it’s not enough for a young person to marry someone from another culture or another country simply for the sake of living in another country. There needs to be some sort of goal they share. They should think twice, because love will get you into trouble. On some level, I just don’t resonate with that sort of easy thinking of an easy marriage.